For dental patients, the work of a dental hygienist shapes the experience of the patient. For Jennifer Sukalski, however, it was her work as a dental hygienist that shaped her interest in dentistry and public health.

“I always liked working with people—whether as a youth counselor or taking care of kids—and as a child I hated going to the dentist,” Sukalski explained. “So, I became a hygienist because I wanted to make patients comfortable in ways that I was not.”

While working as a hygienist in a private practice, Sukalski saw firsthand the barriers that underserved populations faced in receiving high-quality dental care. Whether it involved challenges with transportation, unavailability during standard business hours, or financial barriers, large portions of the US population do not receive any dental care.

During this time Sukalski also began adjunct teaching in Preventive and Community Dentistry at the College of Dentistry, and she later earned a Master’s degree in Dental Public Health.

One of this first projects she worked on examined how the then newly established Dental Wellness Plan (DWP) brought in patients who had never been seen for preventive dental care. The DWP began when the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2014 and Iowa incorporated dental care into Medicaid expansion.

“Many providers had a steep learning curve given the complexity of the DWP, its finances and the dental needs of this previously unserved population,” Sukalski said.

This research and her own experiences working in a private practice gave her a unique perspective on structural barriers facing many Iowans. Her Master’s project on the periodontal treatment needs of the DWP population refined her interest in health disparities, access to care, and patient use of available options.

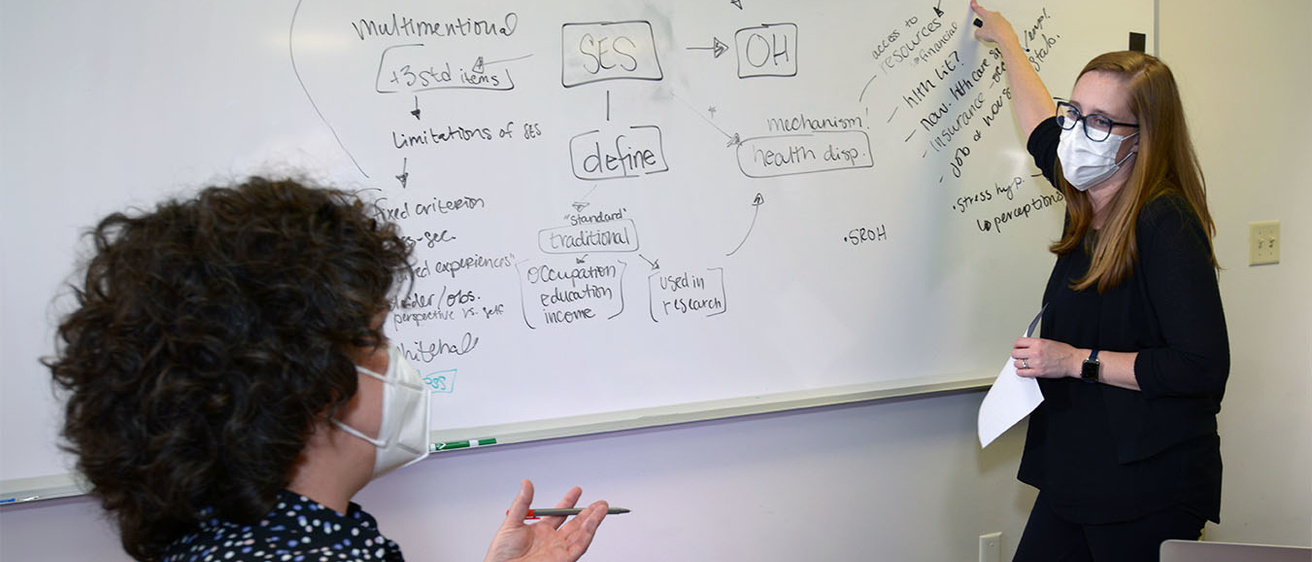

For her dissertation project, Sukalski is investigating the extent to which a person’s own perceived social status affects access to care and health disparities, and she received a F31 award from the NIH to support the project. Most studies of structural barriers to dental care tend to focus on socioeconomic status as the primary barrier to care. This research is powerful but, building on her undergraduate degree from Iowa in psychology, Sukalski is investigating whether it leaves out an important element. Thus, she asks patients to identify where they see themselves on a “social ladder.”

“Seeing where they place themselves on the ladder can capture their life experiences and background better than models that just take into account socioeconomic markers like income, occupation, or education levels,” Sukalski commented.

Sukalski hypothesizes that those who place themselves lower on the social ladder will tend to have less desirable oral health care experiences, but providers can make a difference for these patients and help them come back for care, maintain good oral health habits, and improve outcomes. Sukalski is using one-on-one interviews to help develop a set of tools to help providers improve outcomes for this population.

“Educating our patients and ourselves is important, but developing cultural competency and understanding your patient and what they are going through is also important,” Sukalski said. “As dental care providers, we have to pursue an active and ongoing relationship with our patients and we can’t look down on them or their choices if we want to achieve better outcomes.”

Sukalski already sees three helpful tools. First, we need providers to take financial barriers into account when providing advice and encouragement to patients; second, providers must understand and have compassion for patients as they phase in or out of care for reasons that are largely out of their control; third, patient education requires that a patient and provider reach a shared understanding of that patient’s needs in the confines of a supportive environment. These are all tools for helping patients see themselves as deserving and worthy of dental care—that is, to see themselves further up the ladder, which will have an impact on oral health outcomes.

Overall, Sukalski’s work is aimed at making a difference in the lives of dental patients across the state of Iowa, but she knows her work would not have been possible without encouragement from John Warren, Peter Damiano, and Marsha Cunningham, and without the guidance and support from her mentor, Susan McKernan. She also credits Steve Levy, Brad Amendt, and David Drake for their support of her F31 grant application.

The print version of the original article is contained in the Fall 2021 Dental Link.