Black history month at the College of Dentistry is an opportunity for us to look at our past, celebrate the accomplishments of our esteemed alumni, and drive us to become a more inclusive community for our students, alumni, staff, and faculty. As we look at our past, let us recognize its lasting impact even today.

First Black Graduate of the College of Dentistry

1909

Dr. Rufus P. Beshears (October 12, 1888-October 10, 1961) was the first Black graduate of the University of Iowa College of Dentistry (then the State University of Iowa) in 1909. After three years of study, Dr. Beshears graduated in the top 25% of his dental class of 67 and went on to become a successful dentist in his hometown of St. Joseph, MO.

In 1911, the 23-year old Dr. Beshears applied for appointment as an Acting Dental Surgeon in the U.S. Army. At the time, the U.S. Army did not allow Black people to serve in the U.S. military as physicians or dentists. Although nothing in U.S. law or the military code prevented Black people from serving as dentists in the military, the Surgeon General for the Army, BG Robert M. O’Reilly in a 1904 memorandum written to President Theodore Roosevelt, stated that the military was opposed to their appointment not “because of any abstract question of the rights of the colored race” but instead because of “military efficiency.” (1)

This practice of denying opportunities to Black dentists continued when Dr. Beshears took the examination for appointment as an acting dental surgeon on April 1, 1912 at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, and he was deemed “physically disqualified” for appointment purportedly for a heart condition. (2) It was common practice at the time to use one pretext or another to turn down Black dentists for appointments, even though many servicemen were Black.

This practice changed in 1917 as World War I began, and Dr. Beshears applied again. This time, he was admitted to the Dental Reserve Corps and served as a dental surgeon for the 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated division for Black soldiers. At the time, Black medical and dental professionals were only allowed to provide care for Black troops.

Dr. Beshears returned to St. Joseph, MO, after the war where he continued his dental practice and married a young widow. Kelsey Beshears became a leading civil rights activist in Missouri and the country, and she has a scholarship at Missouri Western State College named in her honor. (4)

1917

Dr. Beshears’ younger brother, William H. Beshears (October 12, 1892-September 6, 1958) also attended the University of Iowa and completed his degree in dentistry in 1917. According to his daughter, he also served in the Dental Reserve Corps. (3) After returning to Iowa City after WWI, the younger Beshears moved to Cedar Rapids and became the first Black dentist in Cedar Rapids where he was the only Black dentist in the city during most of his 40 year career.

Speaking of his decision to go to Cedar Rapids from Iowa City after WWI, Dr. Beshears said that he traveled as far as he could with the money that he had. Some sources seem to confuse the elder and younger Beshears, stating that Dr. Rufus P. Beshears was the first Black dentist in Cedar Rapids.

One of the First Black Female Graduates and Faculty Members at the College of Dentistry

Dr. Rosalie Reddick Miller (December 29, 1925-October 17, 2005) was also a trailblazer at the college. She was the daughter of a dentist in Columbus, Georgia, and she and her husband, Dr. Earl V. Miller, met while in dental school and medical school, respectively, at Meharry Medical College, a historically Black medical school in Nashville, TN.

In 2016, researchers found that over 44% of Black dentists in the US received their dental training at either Meharry Medical College or Howard University College of Dentistry. (5) Thus, alumni from these two schools account for nearly half of all the Black dentists in the US. Today, Black dentists account for approximately 3% of the total number of US dentists, even though Black people make up over 13% of the US population.

After completing dental school in 1951, Dr. Miller and her family moved back to Georgia where she took over her father’s dental practice. While living in Georgia, Dr. Miller and her husband fought against discrimination and segregation and advocated for voting rights.

To continue their careers, Dr. Miller and her family moved back to Nashville in 1956, as her husband pursued advanced education in urology, and she became the director of Dental Hygiene at Meharry. In 1957, the family moved to Iowa City so that Dr. Miller’s husband could continue specializing in urology. During that time, Dr. Miller completed a one-year program in periodontics (this was before the college had its current periodontics certificate program, which started in 1966), and she was a faculty member at the college teaching dental hygiene.

Dr. Richard Bradley, a periodontist who was a fellow student and instructor with Dr. Miller in 1958, described Dr. Miller saying, “Everybody liked her. She had a great sense of humor and the patients loved her.” (December 5, 2005 edition of the DSB Weekly)

The first Black faculty member at the University of Iowa was Philip G. Hubbard who began at Iowa in 1947 as a research engineer in the College of Engineering. (7)

In 1959 after their time in Iowa, Dr. Miller and her family relocated to Seattle. They moved to Seattle because Dr. Miller’s husband was able to secure hospital privileges. Widespread hospital discrimination against Black medical doctors was common until well into the 1960s, even in the Northern US. (8)

Dr. Miller went on to become the first Black woman to practice dentistry in the State of Washington, and she was an assistant professor in the Department of Oral Medicine at the University of Washington. (9)

The older and younger Dr. Beshears and Dr. Miller were important trailblazers for the University of Iowa College of Dentistry.

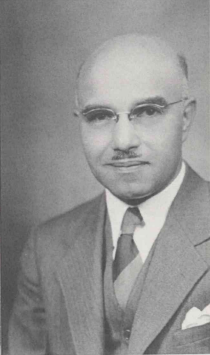

Giving back to Black students: The Dr. Curtis C. Bush Memorial Fund

Dr. Curtis Clyde Bush was a role model for minority students during his time at the University of Iowa and the effects of his presence at Iowa are felt by current students today. Dr. Bush graduated from the University of Iowa in 1927 as one of the first African-American dental school graduates. Dr. Bush moved to Sioux City, Iowa, where he practiced dentistry for 45 years until he passed away in 1974.

That same year, Dr. Bush's widow established the Curtis C. Bush Memorial Fund, but over time, the fund evolved from providing loans to black students to, in 1992, a quasi-endowed scholarship thanks to Dr. Bush's daughter, Judith Bush Dickerson, and her husband, Charles Dickerson who decided to give $1,000 annually to be matched by the AT&T company, equaling $2,000. Mrs. Dickerson graduated from the University of Iowa in 1967 with a bachelor's degree in speech pathology and audiology.

Since 1992, the Dr. Curtis C. Bush Memorial Fund has been awarded to Black or Hispanic students at the college who have shown a financial need and are in good standing with the college.

In 2006, the fund was reviewed and officially changed from a quasi-endowment to a permanent endowment.

One notable recipient of the scholarship is current Clinical Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Student Affairs Sherry Timmons, who received the scholarship in 1992 when the fund was re-established.